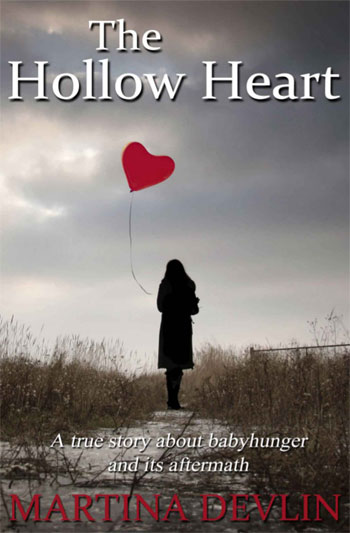

The Hollow Heart

Extract:

I waited for the thud of the front door closing on the floor below, my husband leaving for work. Now I was alone. Propped against pillows in bed, I bent my face towards my stomach and cupped my hands around it. I began to whisper.

‘Stay with me … I need your help … you’ve got to cling to life, you have to want this too … just hold on there as tight as you can … I know it’s hard, I know you’re only tiny. But play your part now and we’ll all have such a life together, I promise. A sunny, sunny life … I’ll be the best mother in the world … I’ll devote myself to you – day and night … you’ll be everything in the world to me … I can’t do it without you … please, babies, please, stay with me … do it for me …Please.’

I was bargaining with my unborn children. Children who were no more than pinpricks of life, just a few cells – so rudimentary they were not even at the foetus stage yet. But who were real to me. They were my babies.

Three embryos had been returned to my body a few days previously, following a course of fertility treatment, and this was the crucial period during which they would seek to implant in my womb. I willed them to succeed, bathing them in love, pleading with them – as though it was a question of choice on their part whether to stay or go. Whether to opt for me as their mother. Or not.

Crouched within the nest of the duvet I stroked my stomach, convinced the rhythmic sweep of my palm would reassure the babies, imagining I was cradling their fragile heads. I crooned a lullaby to them I’d heard as a child, one my sister had sung to her son, too. A lullaby I believed I’d be humming to children wriggling and burping in my own arms soon.

Hush little baby, don’t say a word.

Papa’s going to buy you a mocking bird.

And if that mocking bird won’t sing,

Papa’s going to buy you a diamond ring.

As I murmured to my children I tried to envisage them growing inside me. I pictured them latching diminutive fingers and hooking minuscule toes onto the lining of my uterus. Limpets inside instead of outside the host hull of my body. I didn’t see babies floating within amniotic fluid, tethered to an umbilical cord, as you do in ultrasound scans: I visualised them curling their bodies towards mine and fastening onto me. Hopelessly inaccurate biologically – giggles bubbled through me whenever I conjured up the image. Even now, I find myself smiling at my vision of Velcro babies.

It was five days after the embryo transfer stage of the in vitro fertilisation procedure and I eased out of bed, moving tentatively to avoid jolting my body and dislodging the babies. I went to the window to stare at a tree we’d planted in our front garden the previous year. It was March and a suggestion of spring sprouted on its branches. We’d chosen it to commemorate our unborn babies after the last failed attempt at in vitro fertilisation, IVF. I’d lobbied for a cherry blossom tree – its ephemeral beauty mirroring, for me, the transient lives of those earlier embryos we had lost. Except they weren’t embryos in my eyes, but babies waiting to be born. However my husband, Brian, whose impulses were tidier than mine, had shuddered at the prospect of disorder from the blossom. ‘One gust of wind and it’s scattered everywhere,’ he had protested.

We had settled on a miniature ornamental tree.

As I incubated this current cluster of embryos – the ones who were meant to survive – I wrapped a rug around my shoulders to study the stripling tree, fingers gesticulating in the breeze. It shored up my hopes. ‘Life is meant to be perpetuated,’ I told myself. ‘Plant a tree in soil and it grows, never mind frost or wind or parasites. Human life is meant to survive too.’ I watched the sapling, trance-like, until the cold prodded me back to bed.

When I’d warmed up I slid out from under the duvet again and sidled to the wardrobe, pulling out a bag tucked away at the back. It contained baby clothes I had bought clandestinely a few months earlier: an apricot sleep suit with a floppy-eared rabbit on the breast, a pair of embroidered dungarees, a mint green velour top with rainbow-striped sleeves. If I squeeze shut my eyes and concentrate, I can still feel the texture of the sleep suit between my fingers and hear the pop-pop-pop of its fastenings as they open.

Less frequently during those few days, a pleasure deferred, I had turned to a chest of drawers where, in the lowest one, mummified within layers of tissue paper and hidden beneath my T-shirts, was a damask satin christening robe edged with lace collar and cuffs. There was a matching ivory skull cap with a ribbon to draw under the chin and I visualised my child in it, sombre beneath the frill, like one of those ancient-eyed infants in a cracked oil painting. The petite perfection of this garment captivated me. I scarcely dared touch it: it was sufficient to gaze on its rippling folds and to imagine them filled with a flesh and blood baby. My baby.

Planning for our future as a family was a thrill; it generated an excitement I hadn’t experienced since those years as a small girl on Christmas Eve, struggling to stay awake to catch Santa Claus in the act. I wanted to wrap my arms around my knees and draw them close to my diaphragm, hugging myself with joy. But I was loath to move an unnecessary muscle in case it harmed our embryos.

I whiled away hours musing over how the adjoining bedroom could be redecorated as a nursery. Anticipating a cot with at least one, maybe two, and even – did I tempt fate by hoping for such largesse? – three babies in it. I was unwilling to surrender even one of them. I debated the nursery’s décor: a frieze of jungle animals around the dado rail, perhaps, and a rocking horse in the corner. I’d always had a fancy for a dappled grey wooden stallion, with a flyaway mane for dimpled fists to grip and a scarlet saddle for bouncing on. I had loved its twin during my first year at school, when it had waited for me on the fringes of the classroom until playtime was called.

So I lay there in our double bed, spinning my web, sketching a future crammed with children’s birthday parties, trips to the pantomime, Irish dancing classes and bucket and spade holidays. Father, mother, babies. A family at last.

For fifteen days I fantasised as I rested in bed, trying to give my embryo-babies the best chance of life. The hospital had recommended two days, as a precaution, but I was determined to ease their path into the world by whichever means I could. If necessary, I’d gladly have spent nine months flat on my back memorising every bump in the ceiling. Nothing seemed too steep a price to pay for motherhood. Put my life on hold? I had already been treading water for the past three years, another nine months would make no difference.

When Brian would arrive home from work he’d perch beside me on the mattress and hold my hand. ‘How are you feeling?’ he’d check, lantern-jawed with concern. I’d rally him, insisting everything was fine and we were going to be lucky this time. It was our turn to have a baby. Then he’d relax and we’d watch television, drinking tea and eating biscuits in an oasis of intimacy, the frustrations of the past months at bay. I was certain that our patience and perseverance would soon be rewarded – and Brian’s confidence was bolstered by mine. Soon our lives would be back on track.

I had already chosen three names for our babies. I had not discussed them with Brian, not because I sought to exclude him, but because I knew he would be exasperated by such presumption. Certainly it was bold to the point of foolhardiness, naming children whose existence had not yet been confirmed by the thin blue stripe of a pregnancy test. But I could not afford to wait for them to push their way into the world. I named them right from conception, because names made real children of these three specks inside my body.

Finbarr, Rory and Molly.

Their sex had been determined, even at this early stage, and I guessed I was carrying two boys and a girl. Mother’s intuition. There were extra names on standby – just in case mother’s intuition proved wrong. I named my trio in the hopes my conviction would reinforce theirs. ‘If you’re named you must know you’re wanted,’ I reasoned, and no children could be wanted more than mine.

Names have always been important to me. As a child, I chose books where I liked the characters’ names: tomboy Jo who resisted being a Josephine in Little Women; the exoticism of Pippi Longstocking; Just William’s irritating neighbour Violet Elizabeth Bott, whom I always called Violent Elizabeth for the force of her tantrums. My three passengers would have to be introduced to Jo, Pippi and Violet Elizabeth.

I kept a book of children’s names under my pillow, checking their connotations – the Fionn of Finbarr means blond, and I surmised that at least one of our boys would be fair since the colouring ran in my family. My father and two of my brothers were fair. Maybe Rory would have red hair and freckles like me. Perhaps Molly would be dark like her father – I hoped she’d have his smile too. I loved the way my husband’s smile lit up his face. Sometimes I juggled the combinations in my parallel universe, beguiled by the permutations. Finbarr, Aidan and Molly, perhaps? But always I returned to Finbarr, Rory and Molly. Quite simply, those were the names that belonged to them.

I pressed my hands to my stomach and spoke to my passengers during those days while I waited for doctors to confirm their existence. For myself, I required no corroboration. I called my babies by name as I described to them how happy we would be together in this empty, echoing house that needed their scampering footsteps to awaken it.

This was a time of ripening contentment, despite the intensity of my craving. A period when I believed anything was possible. Daily life, which had stilled during these past three years when I had tried to become a mother, would thrum into activity again. I was convinced that the force of my longing for motherhood had finally surmounted every obstacle. Above all, it had prevailed over the most bewildering impediment: my infertility.

I wasn’t nervous that I might miscarry, although in truth I should have been petrified. Already I had lost a total of seven embryos. But I locked away memory and its corollary, fear, and I concentrated – dear God, how fiercely I concentrated – on believing it would work this time. I was a seven-stone incubator of unequivocal certainty. In less than nine months I would be a mother. Every shred of willpower was trained on this result. I was suffused with blind faith, propelled by something I struggle to define. My absolute conviction was predicated on a visceral compulsion to reproduce – need, then, becoming the driving force.

Percolating through this tunnel vision was the Catholic ethos of my childhood, which promised recompense would follow suffering. Pain purified and prepared a person for reward, that’s what I’d been taught. I seized on this theology, rationalising that since I had withstood so much already, endured my purgatory, paradise must now be within my grasp. My babies would live because they had to live – because I had tolerated a barrage of disappointment to reach this stage. A positive result was as inevitable to me as the rising sun or the incoming tide.

As I lay in bed for a fortnight hatching my embryos, I refused to believe that fate could be so malevolent as to deny me even one of these babies from the ten I had carried. By this stage, my third IVF attempt in a year, I had driven my body to its most far-flung parameters. Perhaps even beyond them. It wasn’t just my body, subjected to a cocktail of drugs, which had been sacrificed. I had also forfeited control over my emotions, my mental health and my self-esteem to this yearning. To this baby hunger which burrowed into every cell of my body and wound its demands around every organ – my spleen, liver, kidneys. My hollow heart.

Our marriage, I knew, was becoming increasingly unstable, pummelled by the impact of successive IVF treatments – and by the demoralising aftermath of failure. Assisted reproduction, as the medics refer to the in vitro fertilisation process, is a cornucopia of possibilities. But it has a shadow side, too, and neither my husband nor I were prepared for it. For the blows to us as a couple, or to our perceptions of one another, which started to waver, the further into this hopeful-fearful world we ventured.

As I rested in bed, however, our volatile arguments immediately prior to the treatment had receded from my memory. Stress had undermined the harmony between us, I told myself. I fooled myself that the children – for which we had both been impatient, starting out, and for which we were by now desperate – would repair the frayed relationship. I believed this as fanatically as I believed I was born to be a mother. I believed because I wanted both to be true. Children would arrive and life would be restored to its pre-IVF harmony. Self-deception was an art I honed during these years.

I had been miserable for so long, awaiting the arrival of the children I craved, but during the incubator weeks nurturing our embryos I was happy again. I’d forgotten what joy felt like, so enmeshed had I become in the mechanics of in vitro fertilisation. The sense of relief at experiencing such an emotion again was rain on my parched soul. My body had betrayed me before, but I could forgive it now because it was finally about to fulfil its function.

Awash with hormones as a result of the fertility treatment, I even felt like an expectant mother. My breasts had swelled, the nipples darkened, and the area around my stomach was sensitive to the touch. I welcomed each twinge, every suggestion of nausea; I was impatient for morning sickness, for stretch marks, for back-ache.

I ate hardly anything during the day, apart from snacks Brian left for me in the bedroom. I was wary of descending the two sets of stairs and tracking the length of the hallway to the kitchen at the back of our terraced house. I was even more hesitant to scale that Kilimanjaro of stairs again. I preferred to remain motionless. Who knew how the babies would react to being juggled around? It might dislodge their cautious hook and eye catch on my womb. Instead I used a kettle in the bedroom to make tea. Often the novel I was reading would slide from my hand, for my own fictional world, which I was busy refining, was more satisfying than any author’s. ‘Everybody well and happy? All my babies holding on tight?’ I’d sing out, gently patting my stomach.

Molly would be the assertive one, keeping her unruly brothers in check. Finbarr would be the creative son and Rory the garrulous extrovert. Or maybe I had it totally wrong. It didn’t matter – I was looking forward to making my children’s acquaintance, whatever their traits.

I was never lonely – the babies were company enough.

Although I was contented within my cocoon, I suppose I was isolated. Perhaps that’s why I wove my reverie in such detail. No family members lived nearby who could visit, and because I was recently returned to Ireland after more than a decade in England, I had few friends.

Sometimes my mother or sister would ring during the day for a chat, anxious that time might be passing slowly for me and causing me to mope. But there was never any drooping. I was growing more secure as each day passed, so confident that I’d plot dates with my sister Tonia, trying to guess the babies’ star signs and their mannerisms. They’d be due towards the end of the year in November. ‘Let’s hope they’re not Scorpio like me,’ she’d joke. ‘They’ll have a sting in their tails. Try to have Libra children, even if they arrive a little early.’ My mother was more prudent during her calls, or perhaps more superstitious, guarded against tempting fate. She’d check I was well and not too bored, and send her love.

Then came the evening when I walked to the bathroom, touching the landing walls for support. I was light-hearted, for as each day passed I had more reason to be optimistic. In another day I’d be returning to the fertility clinic to confirm what I already knew instinctively: I was pregnant. I wondered how long before they could detect the number of pulses beating inside me, still reluctant to surrender even one of our embryos. Two babies would be heavenly, but three would be more heavenly again. I dreamed extravagant dreams: three babies in my life.

Brian was home from work and channel-hopping in the bedroom as the theme music from Coronation Street trailed me along the landing. I set one cautious foot in front of the other, inching along, because I had no intention of tripping. A circumspect shuffle had become second nature to me.

I reached the bathroom and sat down, distracted at realising I’d missed a brother’s birthday. I made a mental note to send him a belated card. Glancing casually into the porcelain below, I glimpsed a smear of blood in the bowl. I stared at it, willing it to be a trick of the light. The near-black blood gleamed against the white. Irrefutable. Yet I could not believe; I touched myself and held up my fingers to my eyes, so close they blurred. My fingertips were rosy.

After what seemed an eternity I stood, icy in my composure, although I needed to grip the wash-hand basin for support. I made certain to do it with my right hand. My left hand, the stained one, I extended at full-length from my body, its fingers splayed. Automatically I moved to pull the lever but could not bring myself to do it. I was not ready to flush away these almost-lives.

‘Brian,’ I croaked, ‘come quickly.’

His face appeared in the doorway, unsuspecting. I wondered at him that he did not realise, simply by looking at me, how our universe had tilted on its axis. But he seemed normal. I gazed at him helplessly and regretted the pain he was about to experience. Time seemed to come to a standstill, as I resisted seeing that untroubled expression crumple. As soon as I spoke Brian would be overwhelmed by sorrow and I wanted to delay it – to spare him a few seconds more of our misplaced faith.

Then I stretched out my hand for him to see the smears of blood.

‘I’ve lost them. Our babies are gone.